What is a 4-day working week and does it really work?

What is a 4-day working week and does it really work?

There’s been plenty of interest, articles and debate in the media and press recently on 4-day working weeks. The idea has reached a new level of interest with the Labour Party in the UK making a pledge to reduce the average working week to 32 hours if they win the next General Election. As a concept, is it really viable, or too good to be true?

There are recent claims of business benefits to individual health and company performance, while others claim reductions in performance and negative mental health impacts through reduced office based socialising.

Having recently joined the sub-5 day working week crowd I’ve decided to wade in on the debate; examining what it is, how it works, and arguments on benefits and problems associated with the 4-day working week. In the next blog, I’ll explain some of my own experiences after 7 months of sub-5 day working weeks.

What is this 4-day working week everyone is talking about?

The argument is that reducing the working week to 4 days has no negative impact on business productivity and creates a more positive working environment. Reduced working hours are claimed to create both physical and mental health benefits for the workforce, making them happier, less stressed and more productive. As a result, this increased productively makes up for the reduction in working hours, creating an overall benefit to a business and its employees.

There is a slight difference in the framing of the public discussions between the UK and the USA from mainstream online news websites. In the UK, the argument appears to focus on reduced working hours overall, in most cases by a full working day in the week; while in the US, the conversation appears to focus more on compressed hours, where an employee works as many hours as they would normally work in a week, in just 4 days. This doesn’t reduce the amount of time a person has at work in total, but does give them an additional day off. For example, this CNN article: Four day work weeks sound too good to be true. These companies make it work (July, 2019).

Where has this idea come from?

The concept isn’t exactly a new. In the 1930s, the seminal economist John Maynard Keynes envisioned a world where by now people would only be working a 15-hour week, spending the rest of the week at leisure (John Maynard Keynes, 1930).

It won’t be a surprise to anyone that this hasn’t happened (although there are those that argue that it did, in fact, arrive but we’ve all just chosen to work longer hours to attain more material wealth). Further, what may surprise people is that since 2010 people in the UK have been working more hours, not less. To make matters worse, adjusted wages as of 2019 are still below levels a decade ago. Put simply, in the UK people are working more hours for less (at least it’s still better than working hours in late 1980s /early 1990s).

Despite this increase in working hours, the UK is still less productive than many similar developed nations, especially across Europe. People are working longer hours than they were a decade ago, earning less than they were a decade ago, and UK productivity is still behind other similar economies. Britons work on average 1,514 hours each annually, four weeks more than in Germany, but are less productive.

What are the benefits of a 4 day week?

The arguments for the benefits of a 4-day working week are starting to gain traction as the concept moves from theory into practice, with companies trialling 4-day working weeks and sharing their evidence.

A Guardian article from March, 2019 provides an example of a company named Indy Cube, which has adopted a 4-day working week for its employees, remarking on it’s ‘productivity boost for bosses and happiness for workers’ (Guardian, March 2019).

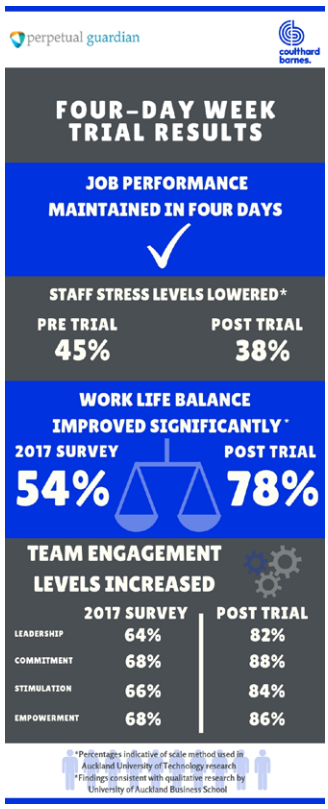

A wider study has been conducted over 8 weeks with Perpetual Guardian, a New Zealand based financial services company (reported in the Guardian, in February 2019 with the headline: Four-day week: trial finds lower stress and increased productivity). The company introduced a 4-day working week, opening up the trial to monitoring by the University of Auckland and Auckland University of Technology. The trial demonstrated improvements in staff commitment and empowerment with reduced reported stress levels (down from 45% to 38%), improved work-life balance scores (up from 54% to 78%).

Beyond wellbeing, Perpetual Guardian employees reported their teams were stronger and functioned better together, more satisfied with their jobs, more engaged and they felt their work had greater meaning. They also reported being more committed to the organisation and less likely to look elsewhere for a job.

On the productivity side, the move to a 4 day week resulted in a 20% rise in productivity – easily making up for the 20% reduction in working hours (Guardian, February 2019).

You can find the study into Perpetual Guardian fully available at https://4dayweek.com/productivity/, which provides a full account of the challenges, benefits and evidence identified in the study.

There are other additional benefits of a 4-day working week expounded, such as reduced congestion, increased energy efficiency and reduced fuel bills, which to my mind are nice, but could also be achieved through other new ways of working techniques.

Arguments against a 4-day working week: Challenges and problems

The concept is not available in all industries –

First of all, the ability to work a 4-day working week could not be available to everyone in all sectors. There are certainly industries that simply could not operate on a 4-day working week, so this conversation is moot. For example, if an individual works on an efficient manufacturing assembly line, it’s unlikely they can take a day off and still produce the same numbers of completed products without increasing the output of the assembly line somehow. Even if you could ‘turn-up’ the speed of the conveyor belt and churn out more, you’d have to adjust your whole logistical supply chain and be willing to have a factory idle for an additional day, or employ more people to keep it running. And for the business, why not increase this productivity over a full working week and be even more efficient?

Is productivity increase sustainable?

The biggest concern from an employer’s point of view is ensuring that the introduction of a 4-day week policy doesn’t lead to increased complacency. While productivity appeared to increase by 20% in the test cases, what’s to say that productivity wouldn’t drop back to the previous norm? In fact, the Perpetual Guardian study indicated that the greatest increased in productivity were experienced in the first few weeks, with productivity falling slightly in the subsequent weeks (Guardian, Feb). With these time limited tests, who’s to say productivity wouldn’t drop further?

Will commitment continue if mainstreamed?

Recent studies have also indicated an increased level of company commitment from employees, no-doubt ecstatic at effectively being given an additional day off per week with no reduction to salary. In a world where this is the exception to the rule, of course employees will be more committed to their employer, anywhere else they’d effectively have to accept 20% increase in working hours for the same level of pay. If the 4-day week caught on and became the norm, can we expect that same level of commitment? I somehow doubt it.

Can it really solve stress?

An article by Adrian Moorhouse in the Independent (April, 2019) provided a wholly different view, taking the line that the UK’s stress epidemic won’t be solved by a 4 day week. The article argues that one of the biggest issues contributing to a rise in unmanageable levels of stress amongst UK employees is too little support from management. When asked, 56% of respondents in a stress study in the UK felt that their business doesn’t provide them with the resources to cope with negative feelings at work – this lack of support won’t be solved by a 4-day working week – in fact, it may result in 20% less opportunity to engage with and seek support from managers.

Moorhouse argues that shortening hours is not the silver bullet. It’s just condensing the same issues, the same stresses and the same negative working cultures into a shorter time-frame. What we should instead, he argues, is to focus on an overhaul of negative corporate cultures, promoting healthy workplaces and giving employees the skills and strategies to effectively manage stress, rather than giving an extra day off to recover from it in the first place.

Conclusions

The jury is still out at the moment, but there’s an increasing body of evidence to show that a 4-day working week could be a positive change.

I’m especially interested in the evidence from practice that show the corresponding increase in productivity that comes with reduced hours (while maintaining pay).

It’s appears true that these working arrangements wouldn’t fit every sector and every business, but that’s the same across the board, different sectors do have different working arrangements and expectations, the fact that we’re looking solely at a 9-to-5 office environment doesn’t make this concept any less viable.

Indeed, introducing a 4-day working week on its own isn’t the solution – Perpetual Guardian also recommends: having clear business productivity guidelines, flexible company culture, management and staff buy-in and regular review of outputs as essential criteria for the successful implementation of a 4-day working week policy. These aren’t just things you can simply write a policy for, but could take many years to transform.

I have my own, largely positive experiences of working a sub-5 day working week which I’ll go into on my next entry.

References:

BBC: Labour Party conference: McDonnell promises four-day working week, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-49798357 (23/09/2019)

Katheryn Vasel, CNN: Four day work weeks sound too good to be true. These companies are making it work, https://edition.cnn.com/2019/07/01/success/four-day-work-week/index.html (01/07/2019)

Adrian Moorhouse, The Independent: Britons do work the longest hours but a four-day week is not the answer – this is what we should do instead, https://www.independent.co.uk/voices/working-hours-britain-eu-brexit-jobs-work-a8877551.html (20/04/2019)

Robert Booth, Guardian: Is this the age of the four day week?: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/mar/13/age-of-four-day-week-workers-productivity (13/03/2019)

Robert Booth, Guardian: Four-day week: trial finds lower stress and increased productivity, https://www.theguardian.com/money/2019/feb/19/four-day-week-trial-study-finds-lower-stress-but-no-cut-in-output (19/02/2019)

Phillip Inman and Jasper Jolly, The Guardian: Productivity woes? Why giving staff an extra day off can be the answer https://www.theguardian.com/business/2018/nov/17/four-day-week-productivity-mcdonnell-labour-tuc (17/11/2018)

Anushka Asthana, The Guardian: Flexibility at work isn’t just about women – men want more from family life, too https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/mar/23/flexibility-at-work-isnt-just-about-women-men-want-more-from-family-life-too?CMP=Share_iOSApp_Other (23/03/2019)

Nicole Lyb Pesce, New York Post: Proof that a four-day work week makes us better employees, https://nypost.com/2018/07/23/proof-that-a-four-day-workweek-makes-us-better-employees/ (23/07/2019)

Kelly Creighton, HR Daily Advisor: Should you implement a 4-day week? https://hrdailyadvisor.blr.com/2019/04/02/should-you-implement-a-4-day-workweek/ (02/04/2019)

CK Clinical: The pros and cons of a 4-day work week https://ckclinical.co.uk/the-pros-and-cons-of-a-4-day-work-week/ (05/10/2019)

4 Day Week: White Paper: The Four-Day Week; Guidelines for an outcome-based trial – raising productivity and engagement https://mistofmanagement.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/5edd8-four-dayweekwhitepaperfebruary2019final.pdf (February, 2019)

John Maynard Keynes (1930), Essays in Persuasion, Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren: New York: W.W.Norton & Co., 1963, pp. 358-373 (available: at Yale University economics website here: http://www.econ.yale.edu/smith/econ116a/keynes1.pdf)

Thank you! Thought it was about time I got back to this, especially since I’m only working 3 days a week now, I should be using that additional time better

LikeLike

This is so wonderfully written and researched! And great to see the mist in action again! What is a sub-5 day work week?

LikeLike